by S.C. Gruff & K.T. Hodge

A type specimen is a preserved specimen designated as a permanent reference for a new species, new genus or some other taxon. The type is the first specimen bearing the new scientific name, and the one true example of the species. Since they are considered permanent reference specimens, types are the most important specimens in a herbarium; they anchor their species.

The requirement for a type specimen is just one of the many rules for describing a new species. When a taxonomist publishes the description of new species of fungi in a journal article or book, he/she must follow rules set down in the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants.

What does a type specimen look like?

A type specimen usually does not look any different than any other dried herbarium specimen in a paper packet. Some herbaria store their types in a special cabinet or put colored labels on them, but often they are interspersed within the collections as they are in CUP.

CUP holdings of type specimens

Since CUP is a major mycological herbarium, many researchers decide to deposit their types here. We have many types of a very wide variety of fungi — including mushrooms, cup fungi and anamorphic fungi — from all over the world.

Types can be hard to find in the herbarium. Sometimes they’re not marked as types. At CUP, our specimens are not taxonomically filed as they are in most other herbaria. The curator sometimes has to do some literature sleuthing to discover whether a specimen is an unmarked type.

The CUP herbarium collections are very important because we have many type specimens that are represented nowhere else.

How many do we have?

CUP holds over 7,000 types, each with its own story. Read about a few of them in our Type Gallery below.

When the ordinary becomes extraordinary: A new species in our own backyard

Think of a type specimen as a kind of anchor for a species concept. Are you a lumper or a splitter? Splitters are inclined to recognize lots of narrowly defined species; lumpers put all kinds of different-looking things into just a few species. You and I may have different notions of how narrow or broad a species should be, but both of our concepts must include the type specimen. To decide what names go with what species, taxonomists often have to look at types.

For many years when collectors found this yellow to orange capped Amanita species, they assumed it was a small specimen of Amanita muscaria var. formosa or Amanita frostiana. G.F. Atkinson took a closer look, and found that the fungus in our photo differs from both A. frostiana and A. muscaria. Its cap is not striate (it lacks minute radiating furrows); unlike A. frostiana the volva is not ocreate (it doesn’t sheath the base like a stocking); and unlike A. muscaria it has a smooth stem. The spores are different, too. Based on these differences, Atkinson erected a new species, Amanita flavoconia — “the yellow dust Amanita.” The yellow patches or warts on the cap are remnants of the universal veil that once encased the whole baby mushroom like an eggshell. It turns out to be much more common than either of its look-alike cousins.

What appears to be an ordinary mushroom in passing may, in fact, be something new and exciting.

Above photo: G.F. Atkinson

This is G.F. Atkinson’s original photograph of one of two syntypes of Amanita flavoconia. In life, it’s a stately yellow mushroom that is mycorrhizal with forest trees including both conifers and hardwoods. The type specimens were collected near Cornell University in upstate New York. The other syntype specimen wasn’t adequately preserved and was discarded long ago. Alas. The remaining syntype, CUP-A 9963, was designated the lectotype by D.T. Jenkins in 1982.

- Atkinson, G.F. 1902. Preliminary notes on some new species of fungi. J. Mycol. 8:110-119.

- Jenkins, D.T. 1982. A study of Amanita types IV. Taxa described by G.F. Atkinson. Mycotaxon 14: 237-246.

- Tulloss, R.E. & Z.L. Yang. 2004. Amanita flavoconia page of their website The Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales). [links need updating]

How new species are discovered: A new species in our own backyard 2

Tar spot is a common disease of maples. It causes inky black circles on maple leaves — they are the fruiting bodies of a pathogenic fungus. In 1987 there was a bad epidemic of tar spot on Norway maple in upstate New York, leading G.W. Hudler and his colleagues to look closely at the causal fungus. When they compared the disease on Norway maple to that on native red and silver maples, they found marked differences. Careful study led them to believe that tar spot on native maples was caused by a different fungus than tar spot of Norway maple.

Tar spot of Norway maple is caused by Rhytisma acerinum, a fungus that has been well known since 1794. It was described from Europe by the great mycologist, C.H. Persoon. For almost 200 years, tar spot of native North American maples was assumed to be caused by the same fungus. However, Hudler et al. (1998) uncovered differences in host specificity, tar spot diameter, and spore-producing stages. They concluded that our native maples were host to a previously unrecognized species, which they named Rhytisma americanum Hudler & Banik. Following the rules of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN), they designated CUP 65337 (above) as its holotype.

Sometimes undiscovered species are right under our noses.

Above photo: Kent Loeffler

Rhytisma americanum causes tar spot of North American red and silver maples. It was first described by Hudler and Banik, who were the first to recognize that it is not the same fungus that causes tar spot of Norway maple. Our specimen CUP 65337 is the holotype.

- Hudler, G.W., M.T. Banik, and S. Miller. 1987. Unusual epidemic of tar spot on Norway maple in upstate New York. Plant Disease 71: 65-68.

- Hudler, G.W., S. Jensen-Tracy, and M.T. Banik. 1998. Rhytisma americanum sp. nov.: a previously undescribed species of Rhytisma on maples (Acer spp.). Mycotaxon 68: 405-416.

One — and only one — type specimen

Today’s International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN) dictates that there must be a single type specimen for any taxon. The aim of this requirement is to reduce confusion about the proper application of the name: in many cases when there are multiple type specimens, they have later been found to represent more than one species. Ideally, when a species is described, a single holotype is designated by the author. If no holotype exists, repairs are needed: A lectotype may be designated from among several specimens mentioned by the original author. Failing that, a modern author can designate a neotype, a specimen of the same species not examined by the original author.

During his research on Amanita cylindrispora Beardslee, R.E. Tulloss found that any of several different syntype specimens — one here at CUP, two in MICH, and more at several other herbaria — might be considered the type. The syntypes are the original specimens from which Beardslee described the species; the Code requires that one be formally designated the type. Tulloss (2005) selected CUP 25548 as the lectotype for Amanita cylindrispora. He based his choice on the presence of an annotation slip by Beardslee that was clearly marked “part of type,” and the well-preserved condition of the specimen. Now A. cylindrispora is properly typified: every fungal taxon properly has either a holotype, a neotype, or a lectotype.

Above photos: Kent Loeffler; H.C. Beardslee

Amanita cylindrispora Beardslee is a lovely species that occurs in sandy soils of the Atlantic coast from Long Island, NY to Florida and west as far as eastern Texas. Beardslee collected the original specimens in Altamonte Springs, Florida. These photos are of CUP 25548, the lectotype specimen. At left is one of the fruiting bodies as it appears today; at right is Beardslee’s original photo.

- Beardslee, H.C. 1936. A new Amanita and notes on Boletus subalbellus. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 52: 105-106, + Plate 14.

- Tulloss, R.E. & Z.L. Yang. 2005. Amanita cylindrispora page of their website The Genus Amanita Pers. (Agaricales). [links need updating]

When types are lost

It’s a dire situation when a type specimen gets lost, since the type anchors a name and its application. If no duplicate specimens exist to designate as lectotypes, a neotype must be found. It’s generally a good idea to look for a new specimen in the same place from which the species was first described, since that’s most likely to reflect what the original author saw.

One dire type story revolves around a diminutive cup fungus, Pithyella hamata Chenant. Unfortunately, Chenantais’s discomycete specimens were discarded by a French mycologist who felt they had little or no value, leaving this fungus name floating free without an anchor. An intrepid team of Cornell taxonomists set out to remedy this in September 1987. The three collectors, R.P. Korf, T. Iturriaga and W.Y. Zhuang, accompanied by Mme. Françoise Candoussau, traveled to the type locality in Ruffec, France to search for a neotype. At a farm called La Roche they found the host fungus Eutryblidiella, but the fungicolous Pithyella hamata was not found. The next day, however, a few kilometers to the north they were able to collect ample material of Chenantais’s species to designate a neotype (CUP 61819).

With the name safely anchored by a neotype, Zhuang was able to evaluate the taxonomic relationships of this little fungus. She concluded that Chenantais’s P. hamata should be recognized as a subspecies of another taxon. It is now properly known as Unguiculariopsis ravenelii subsp. hamata (Chenant.) W.Y. Zhuang.

Above photo: Kent Loeffler

Here’s the neotype specimen of the cup fungus Pithyella hamata Chenant. (CUP 61819). Now it’s known as Unguiculariopsis ravenelii subsp. hamata (Chenant.) W.Y. Zhuang.

This fungicolous fungus grows over top of its host fungus, Eutryblidiella hysterina, often called Rhytidhysteron hysterinum (the black crust in the background), which itself grows on the twigs of common boxwood, Buxus sempervirens. This fungus was first described from Ruffec, France, at a farm called La Roche.

Scale bar = 0.5mm

- Korf, R.P., T. Iturriaga, and W.-y. Zhuang. 1988. Lost and found: a discomycete pilgrimage. Mycotaxon 31: 85-88.

- Zhuang, W.-y. 1988. A monograph of the genus Unguiculariopsis (Leotiaceae, Encoelioideae). Mycotaxon 32: 1-83.

Preserving the integrity of types: what’s a kleptotype?

A herbarium’s most important specimens are its types. They must be handled very carefully, since these finite samples of fungal material are expected to last forever. When type specimens are loaned, herbaria trust that scientists will use discretion, using only a tiny amount for examination using a microscope. Sometimes mycologists speak of kleptotypes — mostly in a humorous way because this is not a formal term — referring to fragments of type specimens kept without permission of the lending herbarium.

Some have insinuated that E.J. Durand’s herbarium includes many discomycete kleptotypes. The presence of so many types makes Durand’s collection one of the best single places in the world to study the taxonomy of cup fungi. However, the idea that Durand purloined type fragments from other herbaria has been put to rest through a careful examination of his correspondence. He routinely asked for and was granted permission to keep type fragments by his sources.

Today, few herbaria would grant such permission. We ask that borrowers return every bit of the types, including microscope slides made from type specimens, and even GenBank numbers for DNA sequences derived from our specimens.

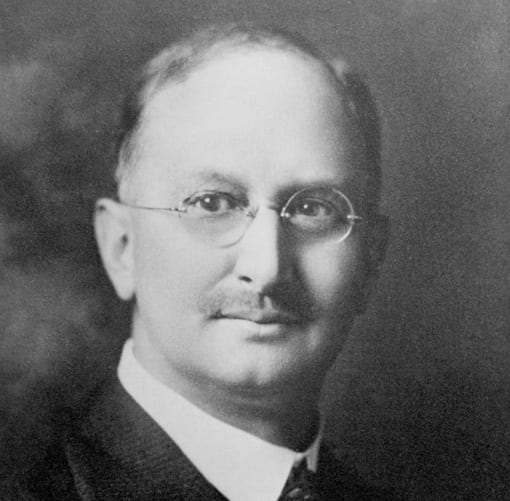

Above photo: W. Fisher

Mycologist Elias J. Durand was a student of the earliest Cornell mycologists, A.N. Prentiss, W.R. Dudley and G.F. Atkinson. In 1896, with a newly minted PhD, he became an instructor under Atkinson for 14 years. He later worked at Missouri University, then the University of Minnesota, where he was chairman of the department of botany from 1920-1921.

Durand was a world expert on cup fungi. Following his death in 1922, Cornell purchased his extensive personal specimen collection. Today his specimens comprise our special collection CUP-D. Durand described 21 new taxa, for which CUP holds 16 types, 27 paratypes and 2 syntypes. His collection also includes about 650 types from other herbaria or authors, making CUP-D a world center for discomycete taxonomy.